Pre-lecture materials

Before class, you can prepare by reading the following materials:

In the previous lesson, we learned how to use git from the command line.

In this lesson, we will learn how to use git remotes and GitHub. As preparation, you can sign up for a GitHub account if you do not already have one.

We will use the local git repository in the planets directory that we created in the previous lesson. If you do not have this any more, please create it by initializing the git repository and adding the set of git commits from the previous lesson.

Acknowledgements

Material for this lecture was borrowed and adopted from

Learning objectives

At the end of this lesson you will:

- Understand git remotes.

- Understand how to use GitHub.

- Understand collaborating and merge conflicts.

Remotes in GitHub

- How do I share my changes with others on the web?

- Explain what remote repositories are and why they are useful.

- Push to or pull from a remote repository.

Version control really comes into its own when we begin to collaborate with other people. We already have most of the machinery we need to do this; the only thing missing is to copy changes from one repository to another.

Systems like Git allow us to move work between any two repositories. In practice, though, it’s easiest to use one copy as a central hub, and to keep it on the web rather than on someone’s laptop. Most programmers use hosting services like GitHub to hold those main copies.

Let’s start by sharing the changes we’ve made to our current project (in the previous lesson) with the world. To this end we are going to create a remote repository that will be linked to our local repository.

Create a remote repository

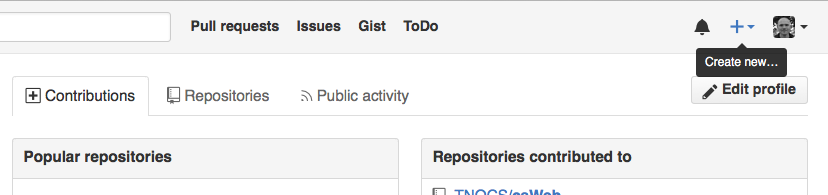

Log in to GitHub, then click on the icon in the top right corner to create a new repository called planets.

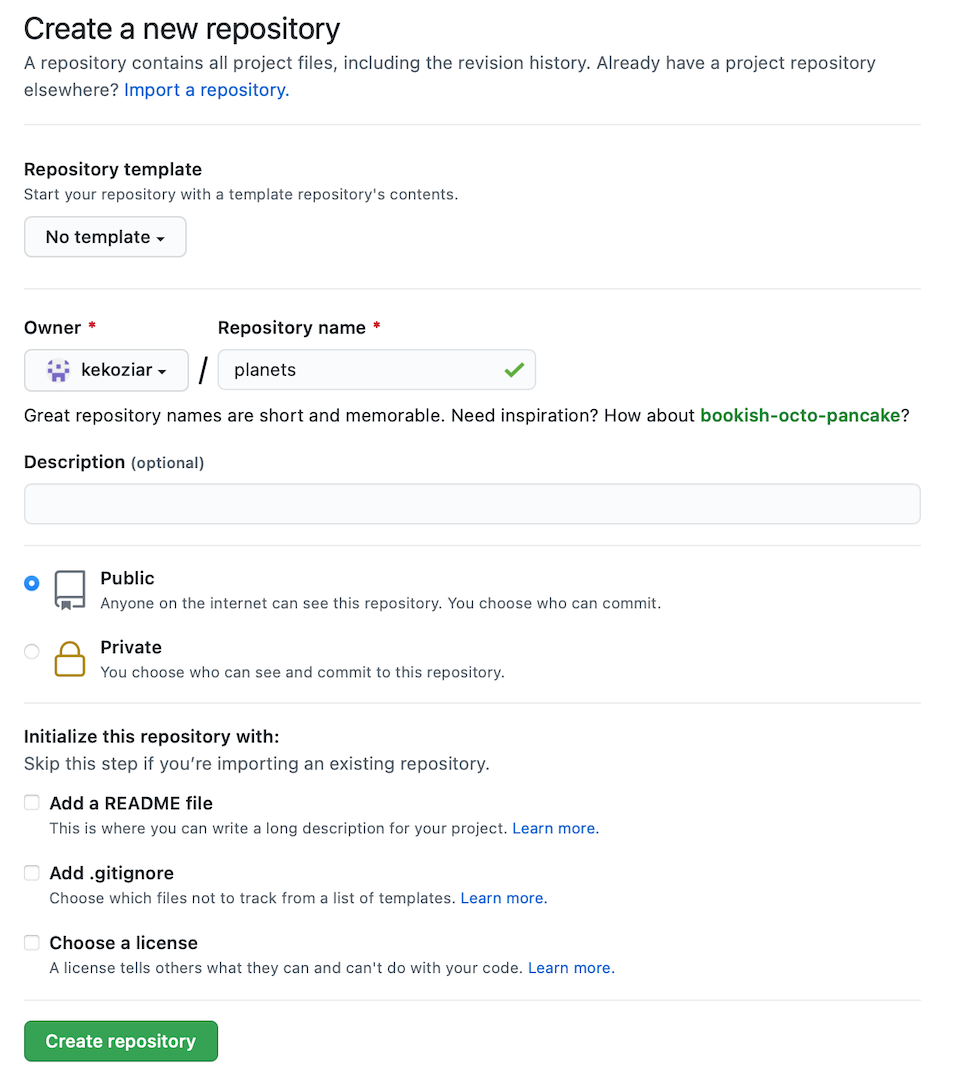

Name your repository “planets” and then click “Create Repository”.

- Since this repository will be connected to a local repository, it needs to be empty.

- Leave “Initialize this repository with a README” unchecked, and keep “None” as options for both “Add .gitignore” and “Add a license.”

- See the “GitHub License and README files” exercise in the Software Carpentry materials for a full explanation of why the repository needs to be empty.

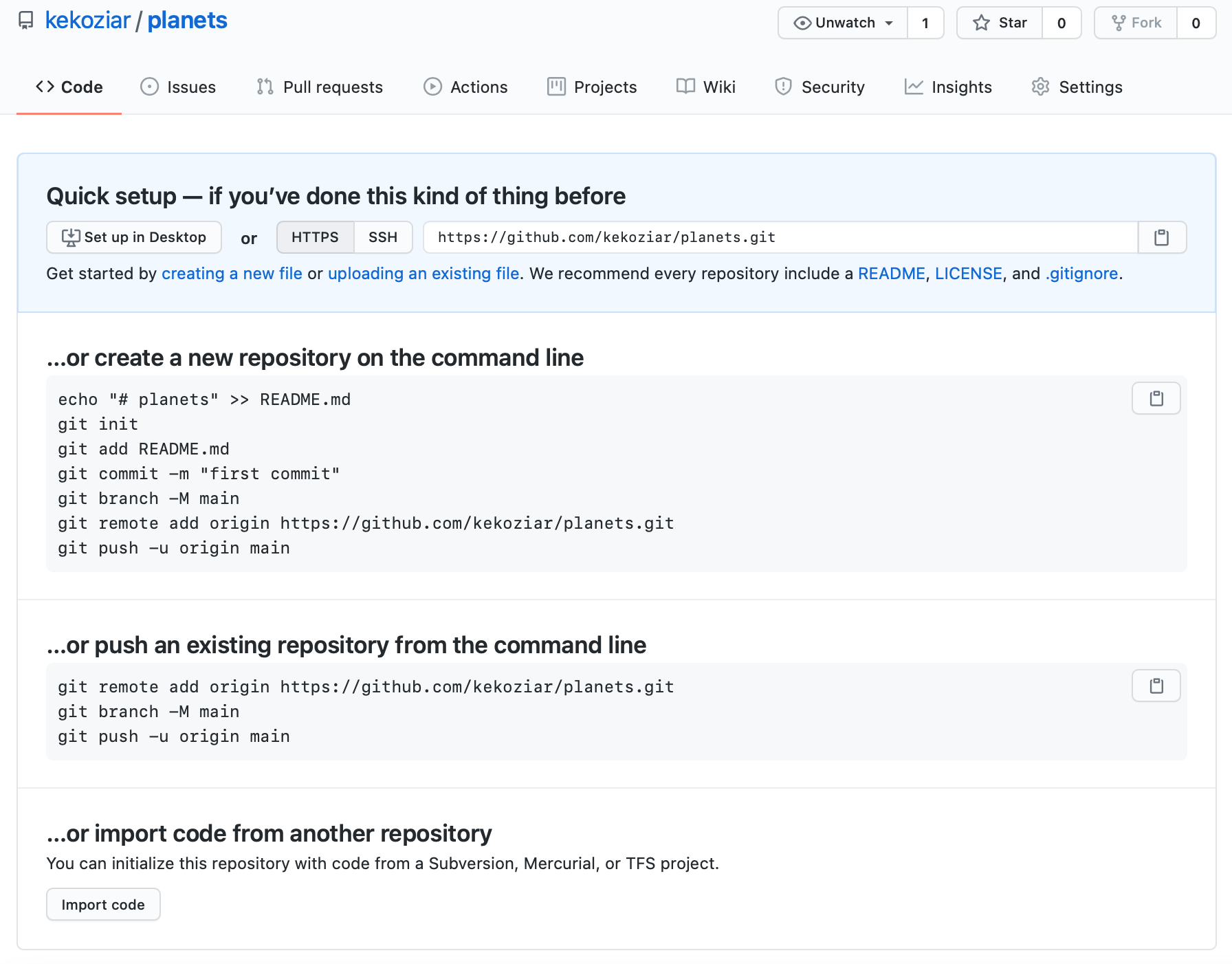

As soon as the repository is created, GitHub displays a page with a URL and some information on how to configure your local repository

This effectively does the following on GitHub’s servers:

mkdir planets

cd planets

git initIf you remember back to the previous lecture where we added and committed our earlier work on mars.txt, you can visualize that process in our local repository like this:

Now that we have created the remote repository, we really have two repositories and this is the idea you should keep in mind:

Our local repository still contains our earlier work on mars.txt, but the remote repository on GitHub appears empty as it does not contain any files yet.

Check that we still have our history of commits in the git repository from the previous lesson:

cd ~/Desktop/planets

git log --onelinec687412 (HEAD -> main) Ignore data files and the results folder.

1507c2a Add some initial thoughts on spaceships

ad5b7d1 Discuss concerns about Mars' climate for Mummy

75a0e21 Add concerns about effects of Mars' moons on Wolfman

cf69058 Start notes on Mars as a baseConnect local to remote repository

Now we connect the two repositories. We do this by making the GitHub repository a “remote” for the local repository. The home page of the repository on GitHub includes the URL string we need to identify it:

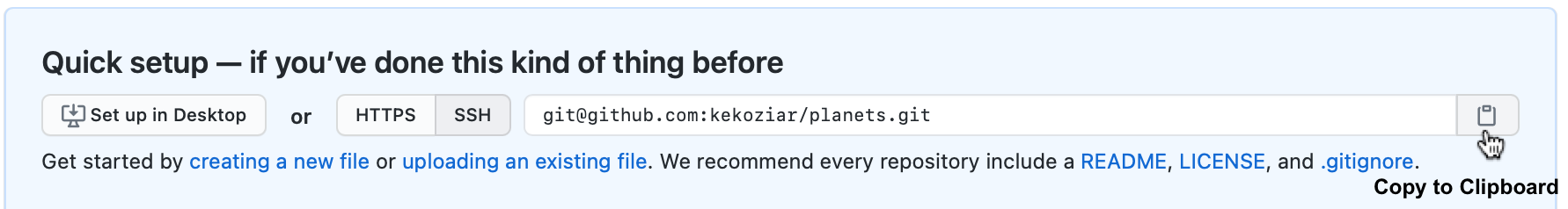

Click on the ‘SSH’ link to change the protocol from HTTPS to SSH.

We use SSH here because, while it requires some additional configuration, it is a security protocol widely used by many applications. The steps below describe SSH at a minimum level for GitHub. A supplemental lesson in the Software Carpentry materials discusses advanced setup and concepts of SSH and key pairs, and other material supplemental to git related SSH.

Copy that URL from the browser, go into the local planets repository, and run this command:

git remote add origin git@github.com:<username>/planets.gitMake sure to use the URL for your repository, i.e. your username.

origin is a local name used to refer to the remote repository. It could be called anything, but origin is a convention that is often used by default in git and GitHub, so it’s helpful to stick with this unless there’s a reason not to.

We can check that the command has worked by running git remote -v:

git remote -vorigin git@github.com:stephaniehicks/planets.git (fetch)

origin git@github.com:stephaniehicks/planets.git (push)We’ll discuss remotes in more detail in the next section, while talking about how they might be used for collaboration.

SSH Background and Setup

Before you can connect to a remote repository, you need to set up a way for your computer to authenticate with GitHub so it knows it’s you trying to connect to your remote repository.

These sections below will not be covered in class, but you are encouraged to set up your SSH key pairs to make your lives easier using git/GitHub!

We are going to set up the method that is commonly used by many different services to authenticate access on the command line. This method is called Secure Shell Protocol (SSH). SSH is a cryptographic network protocol that allows secure communication between computers using an otherwise insecure network.

SSH uses what is called a key pair. This is two keys that work together to validate access. One key is publicly known and called the public key, and the other key called the private key is kept private.

What we will do now is the minimum required to set up the SSH keys and add the public key to a GitHub account.

The first thing we are going to do is check if this has already been done on the computer you are on. Because generally speaking, this setup only needs to happen once.

We will run the list command to check what key pairs already exist on your computer.

ls -al ~/.sshYour output is going to look a little different depending on whether or not SSH has ever been set up on the computer you are using.

If you have not set up SSH on your computer, your output is

ls: cannot access '/c/Users/<username>/.ssh': No such file or directoryIf SSH has been set up on the computer you’re using, the public and private key pairs will be listed. The file names are either id_ed25519 / id_ed25519.pub or id_rsa / id_rsa.pub depending on how the key pairs were set up. If they don’t exist yet, we use this command to create them.

To create an SSH key pair we use this command, where the -t option specifies which type of algorithm to use and -C attaches a comment to the key (here, your email):

ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -C "myemail@email.com"If you are using a legacy system that doesn’t support the Ed25519 algorithm, use:

ssh-keygen -t rsa -b 4096 -C "myemail@email.com"Generating public/private ed25519 key pair.

Enter file in which to save the key (/c/Users/<username>/.ssh/id_ed25519):We want to use the default file, so just press Enter.

Created directory '/c/Users/<username>/.ssh'.

Enter passphrase (empty for no passphrase):Now, it is prompting for a passphrase. If you are using a lab laptop that other people sometimes have access to, create a passphrase. Be sure to use something memorable or save your passphrase somewhere, as there is no “reset my password” option. Alternatively, if you are using your own laptop, you can leave it empty.

Enter same passphrase again:After entering the same passphrase a second time, you receive a confirmation that looks something like this:

Your identification has been saved in /c/Users/<username>/.ssh/id_ed25519

Your public key has been saved in /c/Users/<username>/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub

The key fingerprint is:

SHA256:SMSPIStNyA00KPxuYu94KpZgRAYjgt9g4BA4kFy3g1o myemail@email.com

The key's randomart image is:

+--[ED25519 256]--+

|^B== o. |

|%*=.*.+ |

|+=.E =.+ |

| .=.+.o.. |

|.... . S |

|.+ o |

|+ = |

|.o.o |

|oo+. |

+----[SHA256]-----+The “identification” is actually the private key. You should never share it. The public key is appropriately named. The “key fingerprint” is a shorter version of a public key.

Now that we have generated the SSH keys, we will find the SSH files when we check.

ls -al ~/.sshdrwxr-xr-x 1 <username> 197121 0 Jul 16 14:48 ./

drwxr-xr-x 1 <username> 197121 0 Jul 16 14:48 ../

-rw-r--r-- 1 <username> 197121 419 Jul 16 14:48 id_ed25519

-rw-r--r-- 1 <username> 197121 106 Jul 16 14:48 id_ed25519.pubNow we have a SSH key pair and we can run this command to check if GitHub can read our authentication.

ssh -T git@github.comThe authenticity of host 'github.com (192.30.255.112)' can't be established.

RSA key fingerprint is SHA256:nThbg6kXUpJWGl7E1IGOCspRomTxdCARLviKw6E5SY8.

This key is not known by any other names

Are you sure you want to continue connecting (yes/no/[fingerprint])? y

Please type 'yes', 'no' or the fingerprint: yes

Warning: Permanently added 'github.com' (RSA) to the list of known hosts.

git@github.com: Permission denied (publickey).Right, we forgot that we need to give GitHub our public key!

First, we need to copy the public key. Be sure to include the .pub at the end, otherwise you’re looking at the private key.

cat ~/.ssh/id_ed25519.pubssh-ed25519 AAAAC3NzaC1lZDI1NTE5AAAAIDmRA3d51X0uu9wXek559gfn6UFNF69yZjChyBIU2qKI myemail@email.comNow, going to github.com, click on your profile icon in the top right corner to get the drop-down menu. Click “Settings,” then on the settings page, click “SSH and GPG keys,” on the left side “Account settings” menu. Click the “New SSH key” button on the right side. Now, you can add the title (e.g. using the title “MacBook Air” so you can remember where the original key pair files are located), paste your SSH key into the field, and click the “Add SSH key” to complete the setup.

Now that we’ve set that up, let’s check our authentication again from the command line.

ssh -T git@github.comHi stephaniehicks! You've successfully authenticated, but GitHub does not provide shell access.Good! This output confirms that the SSH key works as intended. We are now ready to push our work to the remote repository.

Push local changes to a remote

After your authentication is setup, we can uuse this command to push the changes from our local repository to the repository on GitHub:

git push origin mainIf you set up a passphrase when setting up your SSH key pairs, it will prompt you for it. If you completed advanced settings for your authentication, it will not prompt for a passphrase.

Enumerating objects: 16, done.

Counting objects: 100% (16/16), done.

Delta compression using up to 8 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (11/11), done.

Writing objects: 100% (16/16), 1.45 KiB | 372.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 16 (delta 2), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (2/2), done.

To https://github.com/stephaniehicks/planets.git

* [new branch] main -> mainIf the network you are connected to uses a proxy, there is a chance that your last command failed with “Could not resolve hostname” as the error message.

To solve this issue, you need to tell Git about the proxy using git config --global.

See the Software Carpentry materials for details.

If your operating system has a password manager configured, git push will try to use it when it needs your username and password. For example, this is the default behavior for Git Bash on Windows. If you want to type your username and password at the terminal instead of using a password manager, type:

unset SSH_ASKPASSin the terminal, before you run git push.

OK, so now that have we used git push, our local and remote repositories are now in this state:

-u Flag

You may see a -u option used with git push in some documentation. This option is synonymous with the --set-upstream-to option for the git branch command, and is used to associate the current branch with a remote branch so that the git pull command can be used without any arguments.

To do this, use git push -u origin main once the remote has been set up.

We can pull changes from the remote repository to the local one as well:

git pull origin mainFrom https://github.com/stephaniehicks/planets

* branch main -> FETCH_HEAD

Already up-to-date.Pulling has no effect in this case because the two repositories are already synchronized. If someone else had pushed some changes to the repository on GitHub, though, this command would download them to our local repository.

- A local Git repository can be connected to one or more remote repositories.

- Use the SSH protocol to connect to remote repositories.

git pushcopies changes from a local repository to a remote repository.git pullcopies changes from a remote repository to a local repository.

Exercises

Browse to your planets repository on GitHub. Under the Code tab, find and click on the text that says “XX commits” (where “XX” is some number). Hover over, and click on, the three buttons to the right of each commit. What information can you gather/explore from these buttons? How would you get that same information in the shell?

The left-most button (with the picture of a clipboard) copies the full identifier of the commit to the clipboard. In the shell,

git logwill show you the full commit identifier for each commit.When you click on the middle button, you’ll see all of the changes that were made in that particular commit. Green shaded lines indicate additions and red ones removals. In the shell we can do the same thing with

git diff. In particular,git diff ID1..ID2where ID1 and ID2 are commit identifiers (e.g.git diff a3bf1e5..041e637) will show the differences between those two commits.The right-most button lets you view all of the files in the repository at the time of that commit. To do this in the shell, we’d need to checkout the repository at that particular time. We can do this with

git checkout IDwhere ID is the identifier of the commit we want to look at. If we do this, we need to remember to put the repository back to the right state afterwards!

Github also allows you to skip the command line and upload files directly to your repository without having to leave the browser. There are two options. First you can click the “Upload files” button in the toolbar at the top of the file tree. Or, you can drag and drop files from your desktop onto the file tree. You can read more about this in the GitHub help pages.

Create a remote repository on GitHub. Push the contents of your local repository to the remote. Make changes to your local repository and push these changes. Go to the repo you just created on GitHub and check the timestamps of the files. How does GitHub record times, and why?

- GitHub displays timestamps in a human readable relative format (i.e. “22 hours ago” or “three weeks ago”). However, if you hover over the timestamp, you can see the exact time at which the last change to the file occurred.

In this lesson, we introduced the git push command. How is git push different from git commit?

- When we push changes, we’re interacting with a remote repository to update it with the changes we’ve made locally (often this corresponds to sharing the changes we’ve made with others). Commit only updates your local repository.

In this lesson we learned about creating a remote repository on GitHub, but when you initialized your GitHub repo, you didn’t add a README.md or a license file. If you had, what do you think would have happened when you tried to link your local and remote repositories?

- In this case, we’d see a “merge conflict” due to unrelated histories. When GitHub creates a README.md file, it performs a commit in the remote repository. When you try to pull the remote repository to your local repository, Git detects that they have histories that do not share a common origin and refuses to merge.

git pull origin mainwarning: no common commits

remote: Enumerating objects: 3, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (3/3), done.

remote: Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), done.

From https://github.com/stephaniehicks/planets

* branch main -> FETCH_HEAD

* [new branch] main -> origin/main

fatal: refusing to merge unrelated historiesYou can force git to merge the two repositories with the option --allow-unrelated-histories. Be careful when you use this option and carefully examine the contents of local and remote repositories before merging.

git pull --allow-unrelated-histories origin mainFrom https://github.com/stephaniehicks/planets

* branch main -> FETCH_HEAD

Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy.

README.md | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 README.mdCollaborating

- How can I use version control to collaborate with other people?

- Clone a remote repository.

- Collaborate by pushing to a common repository.

- Describe the basic collaborative workflow.

For the next step, get into pairs. One person will be the “Owner” and the other will be the “Collaborator”. The goal is that the Collaborator add changes into the Owner’s repository. We will switch roles at the end, so both people will play Owner and Collaborator.

Alternatively, if you are working through this lesson on your own, you can carry on by opening a second terminal window. This window will represent your partner, working on another computer. You won’t need to give anyone access on GitHub, because both ‘partners’ are you.

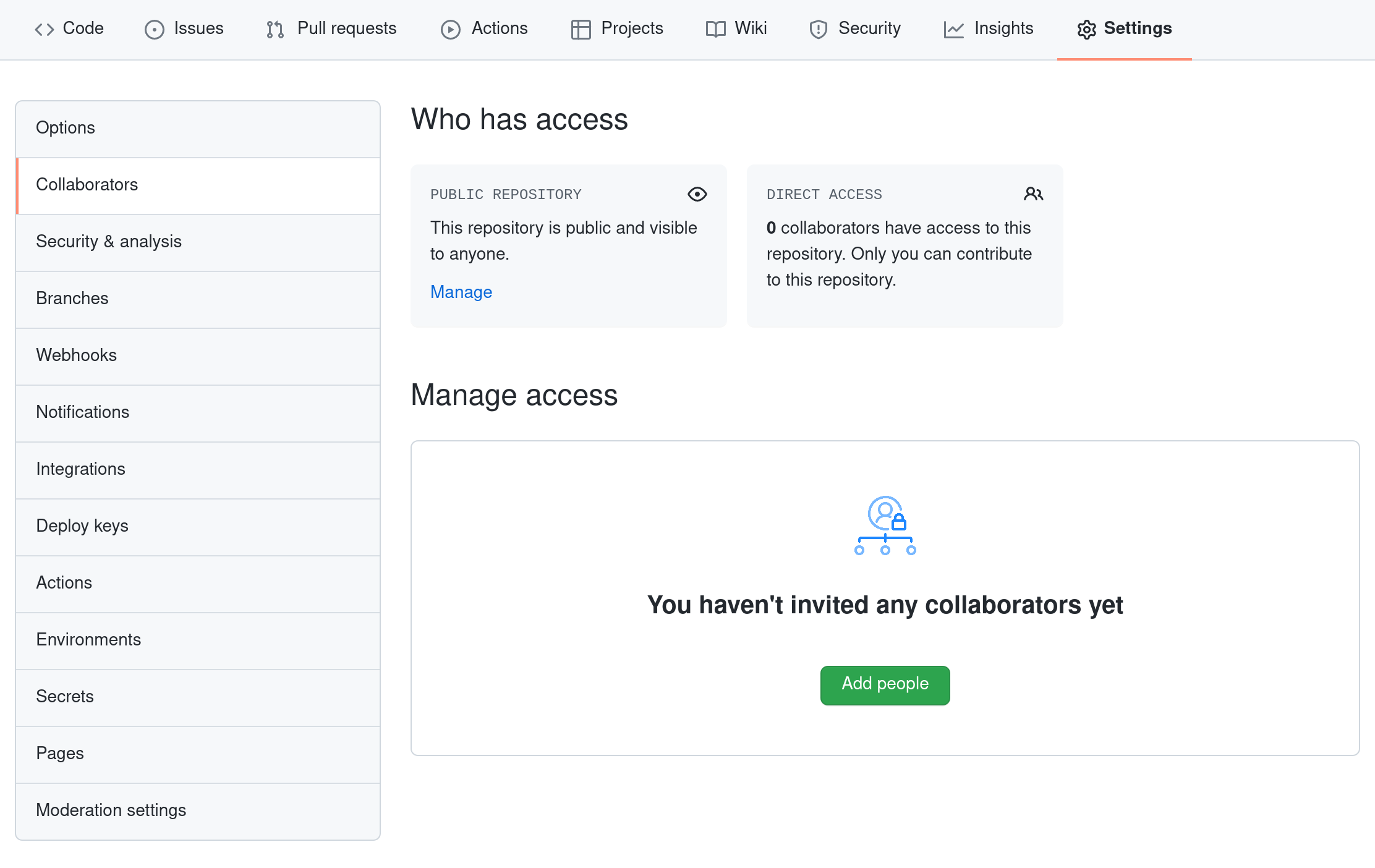

The Owner needs to give the Collaborator access. On GitHub, click the “Settings” button on the right, select “Collaborators”, click “Add people”, and then enter your partner’s username.

To accept access to the Owner’s repo, the Collaborator needs to go to https://github.com/notifications or check for email notification. Once there you can accept access to the Owner’s repo.

Next, the Collaborator needs to download a copy of the Owner’s repository to their machine. This is called “cloning a repo”.

The Collaborator doesn’t want to overwrite their own version of planets.git, so needs to clone the Owner’s repository to a different location than their own repository with the same name.

To clone the Owner’s repo into their Desktop folder, the Collaborator enters:

git clone git@github.com:vlad/planets.git ~/Desktop/vlad-planetsReplace ‘vlad’ with the Owner’s username.

If you choose to clone without the clone path (~/Desktop/vlad-planets) specified at the end, you will clone inside your own planets folder! Make sure to navigate to the Desktop folder first. Alternatively, you can create a directory somewhere else, navigate to it, and run git clone git@github.com:vlad/planets.git (without the clone path).

The Collaborator can now make a change in their clone of the Owner’s repository, exactly the same way as we’ve been doing before.

Create a new file called pluto.txt in the clone of the Owner’s repository, and add the following line to it in TextEdit or Notepad.

It is so a planet!Check from the command line.

cd ~/Desktop/vlad-planets

cat pluto.txtIt is so a planet!Add and commit the changes.

git add pluto.txt

git commit -m "Add notes about Pluto" 1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 pluto.txtThen push the change to the Owner’s repository on GitHub:

git push origin mainEnumerating objects: 4, done.

Counting objects: 4, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done.

Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 306 bytes, done.

Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

To https://github.com/vlad/planets.git

9272da5..29aba7c main -> mainNote that we did not have to create a remote called origin: Git uses this name by default when we clone a repository. (This is why origin was a sensible choice earlier when we were setting up remotes by hand.)

Take a look at the Owner’s repository on GitHub again, and you should be able to see the new commit made by the Collaborator. You may need to refresh your browser to see the new commit.

Thus far, our local repository has had a single “remote”, called origin.

A remote is a copy of the repository that is hosted somewhere else, that we can push to and pull from, and there’s no reason that you have to work with only one.

For example, on some large projects you might have your own copy in your own GitHub account (you’d probably call this origin) and also the main “upstream” project repository (let’s call this upstream for the sake of examples). You would pull from upstream from time to time to get the latest updates that other people have committed.

Remember that the name you give to a remote only exists locally. It’s an alias that you choose - whether origin, or upstream, or fred - and not something intrinsic to the remote repository.

The git remote family of commands is used to set up and alter the remotes associated with a repository. Here are some of the most useful ones:

git remote -vlists all the remotes that are configured (we already used this in the last episode)git remote add [name] [url]is used to add a new remotegit remote remove [name]removes a remote. Note that it doesn’t affect the remote repository at all - it just removes the link to it from the local repo.git remote set-url [name] [newurl]changes the URL that is associated with the remote. This is useful if it has moved, e.g. to a different GitHub account, or from GitHub to a different hosting service. Or, if we made a typo when adding it!git remote rename [oldname] [newname]changes the local alias by which a remote is known - its name. For example, one could use this to changeupstreamtofred.

To download the Collaborator’s changes from GitHub, the Owner now enters:

git pull origin mainremote: Enumerating objects: 4, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (4/4), done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done.

remote: Total 3 (delta 0), reused 3 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), done.

From https://github.com/vlad/planets

* branch main -> FETCH_HEAD

9272da5..29aba7c main -> origin/main

Updating 9272da5..29aba7c

Fast-forward

pluto.txt | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 pluto.txtNow the three repositories (Owner’s local, Collaborator’s local, and Owner’s on GitHub) are back in sync.

In practice, it is good to be sure that you have an updated version of the repository you are collaborating on, so you should git pull before making our changes. The basic collaborative workflow would be:

- update your local repo with

git pull origin main, - make your changes and stage them with

git add, - commit your changes with

git commit -m, and - upload the changes to GitHub with

git push origin main

It is better to make many commits with smaller changes rather than one commit with massive changes: small commits are easier to read and review.

git clonecopies a remote repository to create a local repository with a remote calledoriginautomatically set up.

Exercises

Switch roles and repeat the whole process.

The Owner pushed commits to the repository without giving any information to the Collaborator. How can the Collaborator find out what has changed with command line? And on GitHub?

On the command line, the Collaborator can use

git fetch origin mainto get the remote changes into the local repository, but without merging them. Then by runninggit diff main origin/mainthe Collaborator will see the changes output in the terminal.On GitHub, the Collaborator can go to the repository and click on “commits” to view the most recent commits pushed to the repository.

The Collaborator has some questions about one line change made by the Owner and has some suggestions to propose.

With GitHub, it is possible to comment on the diff of a commit. Over the line of code to comment, a blue comment icon appears to open a comment window.

The Collaborator posts their comments and suggestions using the GitHub interface.

Conflicts

- What do I do when my changes conflict with someone else’s?

Explain what conflicts are and when they can occur.

Resolve conflicts resulting from a merge.

As soon as people can work in parallel, they will likely step on each other’s toes. This will even happen with a single person: if we are working on a piece of software on both our laptop and a server in the lab, we could make different changes to each copy. Version control helps us manage these conflicts by giving us tools to resolve overlapping changes.

To see how we can resolve conflicts, we must first create one. The file mars.txt currently looks like this in both partners’ copies of our planets repository:

cat mars.txtCold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidityLet’s add a line to the collaborator’s copy only:

cat mars.txtCold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

This line added to Wolfman's copyand then push the change to GitHub:

git add mars.txt

git commit -m "Add a line in our home copy"[main 5ae9631] Add a line in our home copy

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)git push origin mainEnumerating objects: 5, done.

Counting objects: 100% (5/5), done.

Delta compression using up to 8 threads

Compressing objects: 100% (3/3), done.

Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 331 bytes | 331.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 3 (delta 2), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (2/2), completed with 2 local objects.

To https://github.com/vlad/planets.git

29aba7c..dabb4c8 main -> mainNow let’s have the owner make a different change to their copy without updating from GitHub (i.e. without the Owner using git pull origin main):

cat mars.txtCold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

We added a different line in the other copyWe can commit the change locally:

git add mars.txt

git commit -m "Add a line in my copy"[main 07ebc69] Add a line in my copy

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)but Git will not let us push it to GitHub:

git push origin mainTo https://github.com/vlad/planets.git

! [rejected] main -> main (fetch first)

error: failed to push some refs to 'https://github.com/vlad/planets.git'

hint: Updates were rejected because the remote contains work that you do

hint: not have locally. This is usually caused by another repository pushing

hint: to the same ref. You may want to first integrate the remote changes

hint: (e.g., 'git pull ...') before pushing again.

hint: See the 'Note about fast-forwards' in 'git push --help' for details.(See illustration on the Software Carpentry website.)

Git rejects the git push because it detects that the remote repository has new updates that have not been incorporated into the local branch.

What we have to do is pull the changes from GitHub, merge them into the copy we are currently working in, and then push that.

Let’s start by pulling:

git pull origin mainremote: Enumerating objects: 5, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (5/5), done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (1/1), done.

remote: Total 3 (delta 2), reused 3 (delta 2), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), done.

From https://github.com/vlad/planets

* branch main -> FETCH_HEAD

29aba7c..dabb4c8 main -> origin/main

Auto-merging mars.txt

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in mars.txt

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.The git pull command updates the local repository to include those changes already included in the remote repository.

After the changes from remote branch have been fetched, Git detects that changes made to the local copy overlap with those made to the remote repository, and therefore refuses to merge the two versions to stop us from trampling on our previous work.

The conflict is marked in in the affected file:

cat mars.txtCold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

<<<<<<< HEAD

We added a different line in the other copy

=======

This line added to Wolfman's copy

>>>>>>> dabb4c8c450e8475aee9b14b4383acc99f42af1dOur change is preceded by <<<<<<< HEAD. Git has then inserted ======= as a separator between the conflicting changes and marked the end of the content downloaded from GitHub with >>>>>>>.

The string of letters and digits after that marker identifies the commit we’ve just downloaded.

It is now up to us to edit this file to remove these markers and reconcile the changes. We can do anything we want: keep the change made in the local repository, keep the change made in the remote repository, write something new to replace both, or get rid of the change entirely. Let’s replace both so that the file looks like this:

cat mars.txtCold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

We removed the conflict on this lineTo finish merging, we add mars.txt to the changes being made by the merge and then commit:

git add mars.txt

git statusOn branch main

All conflicts fixed but you are still merging.

(use "git commit" to conclude merge)

Changes to be committed:

modified: mars.txtgit commit -m "Merge changes from GitHub"[main 2abf2b1] Merge changes from GitHubNow we can push our changes to GitHub:

git push origin mainEnumerating objects: 10, done.

Counting objects: 100% (10/10), done.

Delta compression using up to 8 threads

Compressing objects: 100% (6/6), done.

Writing objects: 100% (6/6), 645 bytes | 645.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 6 (delta 4), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (4/4), completed with 2 local objects.

To https://github.com/vlad/planets.git

dabb4c8..2abf2b1 main -> mainGit keeps track of what we’ve merged with what, so we don’t have to fix things by hand again when the collaborator who made the first change pulls again:

git pull origin mainremote: Enumerating objects: 10, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (10/10), done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done.

remote: Total 6 (delta 4), reused 6 (delta 4), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (6/6), done.

From https://github.com/vlad/planets

* branch main -> FETCH_HEAD

dabb4c8..2abf2b1 main -> origin/main

Updating dabb4c8..2abf2b1

Fast-forward

mars.txt | 2 +-

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)We get the merged file:

cat mars.txtCold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

We removed the conflict on this lineWe dont need to merge again because Git knows someone has already done that.

Git’s ability to resolve conflicts is very useful, but conflict resolution costs time and effort, and can introduce errors if conflicts are not resolved correctly. If you find yourself resolving a lot of conflicts in a project, consider these technical approaches to reducing them:

- Pull from upstream more frequently, especially before starting new work

- Use topic branches to segregate work, merging to main when complete

- Make smaller commits

- Where logically appropriate, break large files into smaller ones so that it is less likely that two authors will alter the same file simultaneously

Conflicts can also be minimized with project management strategies:

- Clarify who is responsible for what areas with your collaborators

- Discuss what order tasks should be carried out in with your collaborators so that tasks expected to change the same lines won’t be worked on simultaneously

- If the conflicts are stylistic (e.g. tabs vs. spaces), establish a project convention that is governing and use code style tools to enforce, if necessary

- Conflicts occur when two or more people change the same lines of the same file.

- The version control system does not allow people to overwrite each other’s changes blindly, but highlights conflicts so that they can be resolved.

Exercises

What does Git do when there is a conflict in an image or some other non-textual file that is stored in version control (e.g. mars.jpg)?

- Git will return an additional warning in the merge conflict message:

warning: Cannot merge binary files: mars.jpg (HEAD vs. 439dc8c08869c342438f6dc4a2b615b05b93c76e)Git cannot automatically insert conflict markers into an image as it does for text files. So, instead of editing the image file, we must check out the version we want to keep. Then we can add and commit this version.

We can also keep both images if we give them different filenames and then add and commit them.

A short example of a typical workflow in an order that will minimize merge conflicts:

- Update local repo:

git pull origin main - Make changes: e.g.

echo 100 >> numbers.txt - Stage changes:

git add numbers.txt - Commit changes:

git commit -m "Add 100 to numbers.txt" - Update remote:

git push origin main

Post-lecture materials

There are other resources available on the Software Carpentry’s website in particularly around:

- The importance of how version control can help your work more open and support Open Science. Open scientific work is more useful and more highly cited than closed.

- What type of licensing should you consider to include with your work on Licensing.

- How to make your work easier to cite with the less on Citations.